Latest album:

Jugendstil

Transcriptions and Paraphrases for piano

My first collaboration with refined French label La Dolce Volta.

How can one come to terms with being a pianist madly in love with Austro-German post-Romantic music, which forsook one’s instrument in favour of the orchestra?

Liszt

Late works for piano

Beatrice Berrut has been walking in the footsteps of Franz Liszt for over 20 years, and after exploring his mature works in Metanoia, and his concertante works in Athanor, it was during the dark period of concert halls’ lockdown that she matured her interpretation of Franz Liszt’s late works.

Liszt Athanor

Piano Concertos no 1 & 2, Totentanz

Athanor: de התנור (ha tanur), the furnace used by alchemists in their search for the philosopher’s matter is indispensable for the maturation of the Great Work.

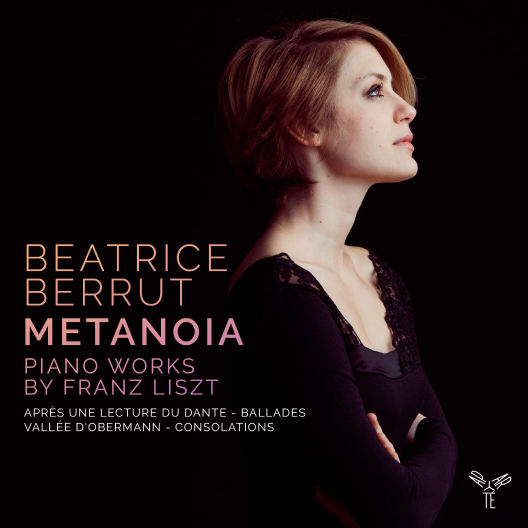

Metanoia

Piano works by Franz Liszt

The world achieves a balance through those conflicting values. And he gives us too the right to be contradictory, inconsistent in our enthusiasms, changing in our moods.

Lux Aeterna

Visions of Bach

The contemplative nature of Bach’s music, its austerity, its simplicity, are deeply moving.

Robert Schumann

The 3 Sonatas for piano

Brilliant from start to finish, the collection of three Sonatas for piano by Robert Schumann represents some of the summits of Romantic piano music – yet, except perhaps for the Second, than Carnaval or the Fantasy which virtuosos love to include in their programmes.